New Immigration Prison

Become Volunteer

Refugee Hearing

Latest Campaigns

Micro Funding

We are launching Ekens Foundation Micro Funding Programme for rural women entrepreneurs. As the founder and president of…

- Raised: $1280

- Goal: $70000

Hunger Campaign

Through our research, we understand that the primary cause of poverty in human life is due to lack…

- Raised: $150

- Goal: $5000

Refugees Incarceration

They are many rejected refugees and asylum seekers in various detention right now, The fact that their application…

- Raised: $20

- Goal: $500

Blogs

Rioters taunt Greek police at Macedonia protest

The Nigeria House of Reps to Probe $446.4m shipping firms’ Demurrage on Imported Petrol

The Nigeria Federal Government accuses opposition Party of planning to use Boko Haram to disrupt the 2019 elections

Cyber Crime Stages in Ukraine Raids in International Probe

Feature Projects

Refugees Bonds

Support Our Immigration and Refugees Bail Bond Programme

- Donators - 28

- Goal - $25400

- Raised - $1300

Here is the detail to fully understand why you should support this program, In Canada, foreign nationals or…

Donate Now Read MoreEvents

Helping the Less privileged, Rejected Refugees and Asylum Seekers Globally

8

Aug

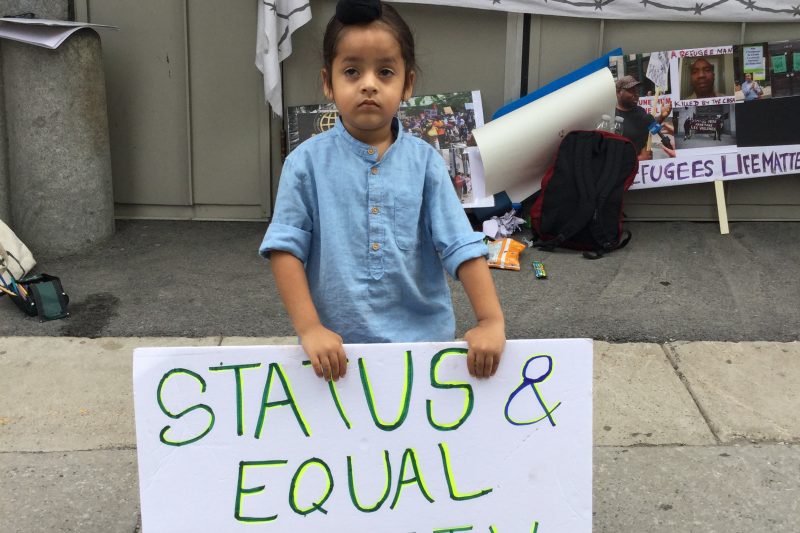

Canada Immigration Status for all rally at Justin Trudeau’s office Montreal

- 11 am

- 1100 Boul Crémazie EMontréal, QC H2P 2X2

Inform the Ottawa Government that Legalizing Refugees and undocumented Immigrants is more Important than the Legalized Weed in Canada Following…

5

Jun

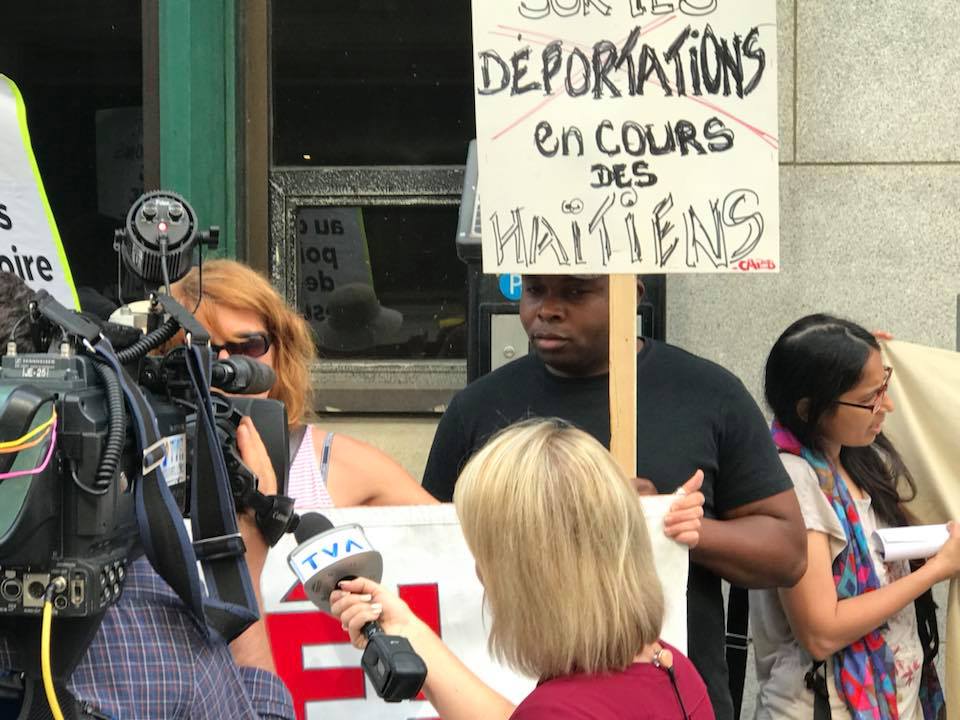

Emergency Immigration Rally for Adama who is currently detained and facing deportation in five days

- 10am - 00am

- 200 René-Lévesque Street West), Montreal

Emergency Immigration Rally for Adama, who is currently detained is facing deportation in five days On June 9,…

12

Feb

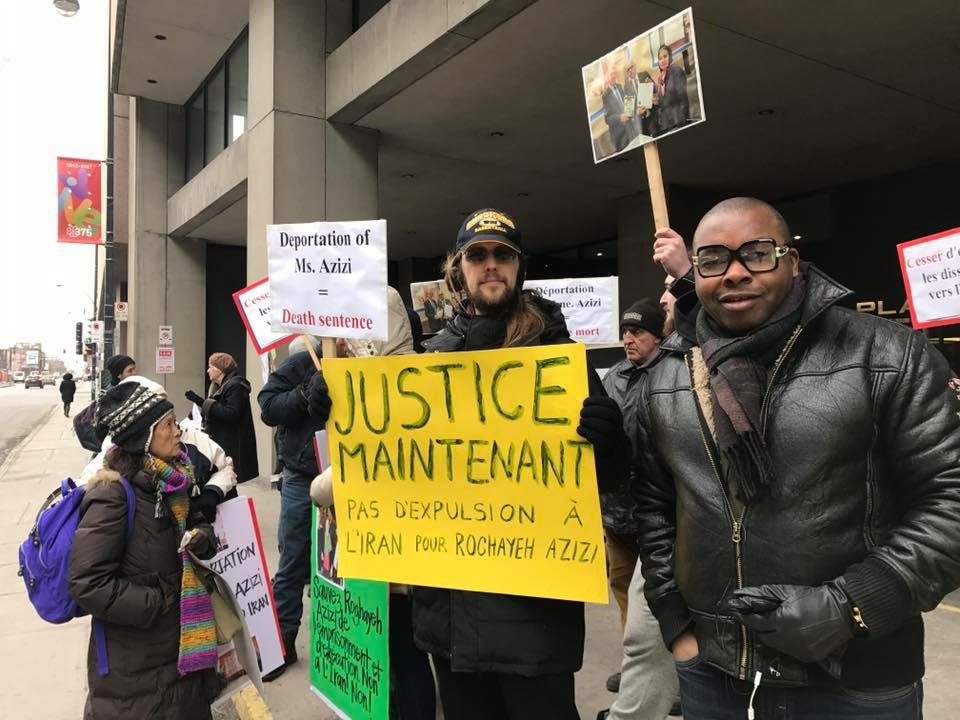

Immigration and Refugees Rally

- 12- pm

- Guy-Favreau Complex (200 René-Lévesque Blvd West).

Join us for rally across Canada on February 12th at 12pm as the health community calls on the…

15

Jan

Political Campaign

- 6:00pm - 8:00pm

- pin 1282 Avenue Bernard, Outremont, QC H2V 1V9, Canada

Be part of the history in Outremont You are hereby invited to an official campaign kickoff of #Rachel…

18

Jun

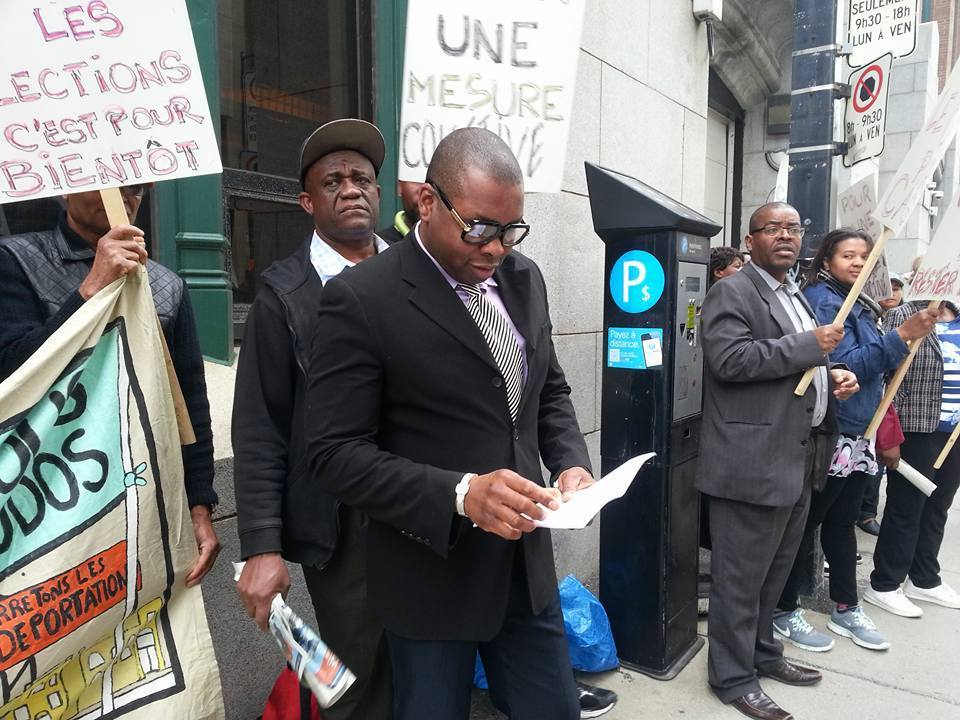

Allied Campaign

- 2:00pm - 4:30pm

- Nelson Mandela Park Plamondon Metro Victoria, Avenue, Montreal, Quebec

This is an allied campaign for the annual Status For All demonstration, in partner with Solidarity Across Borders…

No Amount is small

Message from Ekens Azubuike.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!

Ekens Azubuike is the founder and a board member of the Ekens Foundation International.

as a fortress of retribution for the Canadian state's default action and abandonment of international norms and responsibilities under the nation's law, known as international law

The Canadian State Party's wrongful act against the binding texts that Canada signed, consented to and corrected, such as the 1951 Geneva Convention and its applicable protocols related to international protection

Those wrongful acts of the Canadian state party gave birth to the Ekens Foundation International in conformity with the United Nations Conference on International Organizations, which adopted and ratified the UNCIO Treaty.

Thus, we are a non-soliciting and self-funding international nonprofit organization, Think Thank Civil and Political Rights Advocates, fighting and defending refugees, asylum seekers, and political detainees globally.

Petitioning matters that require the attention of the United Nations Organs, such as individual cases against a state party for wrongful acts, attribution, and responsibilities in violation of the nation's law, also known as international law,

I hope that the Canadian government will one day reconsider the agreed-upon treaty of international law, which they consented to, signed, and ratified into their constitutional law. and stop sending refugees to countries where their people face torture and persecution in violation of the international convention on torture, including the Canadian authority, and stop using the refugee applicant's country of origin and her aggressor as sources of information in the determination of international protection in violation of the United Nations High Commission for Refugee Guidelines.

Volunteer and Recruitment

We are currently recruiting domestic and international volunteers to coordinate our programs in their various local communities.

and in various countries to assist those rejected refugees and asylum seekers.

In our efforts to protect vulnerable refugees and rejected refugees and asylum seekers.

while lobbying the host countries to change their refugee and asylum laws and for them to fully implement the international treaties and resolutions.

such as the 1951 Geneva Convention and its applicable protocols.

International Convention against Torture

International Human Rights Law

International Humanitarian Law

International Refugee Law

However, we are recruiting domestic and international volunteers whose duties would include the evaluation and risk assessment of rejected refugees after they might have exhausted all their domestic remedies in the host countries.

These efforts would enable us to activate our last-minute cross-border justice programmes under the United Nations Optional Protocols on Civil and Political Rights following the international covenant norms.

Whether you are contacting us for intervention in deportation proceedings or you want to volunteer for us, Kindly use the contact form to sign up or send your CV to info@ekensfoundation.org, and our team will get back to you soon.

Principle of Non Refoulment

Hello, my name is Ekens Azubuike, I am the founder and a Board member of the Ekens Foundation International, As a stronghold of the Canadian state wrongful act of retribution such as their default action on responsibilities under the nation's law which is known as international law., The wrongful act of the Canadian State party against the binding text which Canada signed, consented and rectified, such as the 1951 Geneva Convention and its applicable protocols related to international protection.

Those wrongful acts of the Canadian state party gave birth to the Ekens Foundation International in conformity with the United Nations Conference on International Organization as adopted and ratified no (UNCIO) Treaty.

I have taken my liberty to outline here below, the principle of non-refoulment which Canada and other state actors are not only responsible for but are obliged to respect.

The principle of non-refoulement under international human rights law, the principle of non-refoulment guarantees that no one should be returned to a country where they would face torture, cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, and other irreparable harm.

This principle applies to all migrants at all times, irrespective of migration status.

What is the principle of non-refoulment?

The principle of non-refoulment forms essential protection under international human rights, refugee, humanitarian, and customary law.

It prohibits States from transferring or removing individuals from their jurisdiction or effective control when there are substantial grounds for believing that the person would be at risk of irreparable harm upon return, including persecution, torture, ill-treatment, or other serious human rights violations.

Under international human rights law, the prohibition of refoulement is explicitly included in the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) and the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED). In regional instruments, the principle is explicitly found in the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention of Torture, the American Convention on Human Rights, and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

International human rights bodies, regional human rights courts, as well as national courts, have guided that this principle is an implicit guarantee flowing from the obligations to respect, protect and fulfill human rights. Human rights treaty bodies regularly receive individual petitions concerning non-refoulment, including the Committee Against Torture, the Human Rights Committee, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, and the Committee on the Rights of the Child. What is the scope of the principle of non-refoulment?

The prohibition of refoulement under international human rights law applies to any form of removal or transfer of persons, regardless of their status, where there are substantial grounds for believing that the returnee would be at risk of irreparable harm upon return on account of torture, ill-treatment or other serious breaches of human rights obligations.

As an inherent element of the prohibition of torture and other forms of ill-treatment, the principle of nonrefoulement is characterized by its absolute nature without any exception. In this respect, the scope of this principle under relevant human rights law treaties is broader than that contained in international refugee law. The prohibition applies to all persons, irrespective of their citizenship, nationality, statelessness, or migration status, and it applies wherever a State exercises jurisdiction or effective control, even when outside of that State’s territory. The prohibition of refoulement has been interpreted by some courts and international human rights mechanisms to apply to a range of serious human rights violations, including torture, and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, flagrant denial of the right to a fair trial, risks of violations to the rights to life, integrity and/or freedom of the person iii, serious forms of sexual and gender-based violence, death penalty or death row, female genital mutilation, or prolonged solitary confinement via, among others.

Some courts and some international human rights mechanisms have further interpreted severe violations of economic, social, and cultural rights to fall within the scope of the prohibition of non-refoulment because they would represent a severe violation of the right to life or freedom from torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

For example, degrading living conditions vii, lack of medical treatment or mental illness have been found to prevent the return of persons. Heightened consideration must also be given to children in the context of non-refoulment, whereby actions of the State must be taken in the best interests of the child.

In particular, a child should not be returned if such a return would result in the violation of their fundamental human rights, including if there is a risk of insufficient provision of food or health services.

xi How to respond to the protection needs of migrants according to the principle of non-refoulment? States have a legal obligation under international human rights law to uphold the principle of non-refoulment, including ensuring that a range of practical and human rights-based protection mechanisms are in place:

1. Mechanisms for assessment related to the principle of non-refoulment. States should put in place mechanisms and allocate resources to ensure that the IHRL protection needs of all migrants can be assessed individually and with due process, including as a supplement to asylum determination mechanisms.

xii 2. Mechanisms for entry and stay are related to the principle of non-refoulment. States should establish mechanisms for entry and stay for those migrants who are unable to return under IHRL, to ensure the principle of non-refoulment, as well as on other grounds such as ensuring torture rehabilitation.

xiii Administrative and legislative mechanisms should be set up to grant legal status to migrants who cannot return, in the form of temporary, long-term, or permanent status.

xiv For more information, see OHCHR,

What does it mean by protection for migrants?

(2018) OHCHR, Recommended Principles and Guidelines on Human Rights at International Borders

(2014) I ECtHR, Othman (Abu Qatada) v the United Kingdom, No. 8139/09, 17 January 2012, para 235, 258.

ii Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 31, para 12.

iii Inter-American Convention on Human Rights, art. 22(8).

IACtHR, Pacheco Tineo Family v. Bolivia, Judgment of November 25, 2013, para 135.

iv CAT, Njamba and Balikosa v Sweden, No. 322/2007, 3 June 2010, para 9.5;

CEDAW, General Recommendation No. 32, para 23. v Human Rights Committee,

Judge v Canada, No. 829/1998, 20 October 2003, para 10.3;

ECtHR, Soering v the United Kingdom, No. 14038/88, 7 July 1989, para 111.

vi Human Rights Committee, Kaba v Canada, 21 May 2010, para 10.1;

CEDAW, General Recommendation No. 32, para 23..

vii Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 20, 1994, para 6.

viii ECtHR, MSS v Belgium and Greece, 30696/09, 21 January 2011.

ix Human Rights Committee, C v Australia, No. 900/1999;

ECtHR, Paposhvili v Belgium, 41738/10, 13 December 2016,

IACtHR, Advisory Opinion OC-21/14, 19 August 2014, para 229.

x Human Rights Committee, A.H.G. v Canada, No. 2091/2011, 5 June 2015, para 10.4.

xi CRC, General Comment No. 6, para 27 (see also para 84).

xii CAT, General Comment No. 4 (2017) on the implementation of article 3 of the Convention in the context of article 22. Para. 13.

xiii Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture, A/HRC/37/50 26 February 2018, para. 40; CAT,

General Comment No. 4 (2017) on the implementation of article 3 of the Convention in the context of article 22, para 22.

xiv CAT, Seid Mortesa Aemei v Switzerland (1997), Comm. No. 34/1995

Pre and Post Deportation.

We undertake the task is to tracking, monitoring, and documenting the pre and post-deportation of refugees.

The wrongful act of state parties against human rights violations, abuse, torture, and arbitrary detention.

We use such reports to lobby the host governments to change their asylum policies because what happens to refugees in post-deportation is largely unknown as they might be apprehended by their agents of persecution, aggressors, imprisoned, tortured, persecuted, or killed.

These are the facts that evidence is increasing that deported refugees are grossly mistreated by their aggressor as deporting countries do not monitor what happens to them after deportation.

U. N. Refugee Hand Book.

Geneva, January 1992,

UNHCR 1979

FOREWORD

I) Refugee status, on the universal level, is governed by the 1951 Convention and 1967

Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. These two international legal instruments have been

adopted within the framework of the United Nations. At the time of republishing this Handbook

110 states have become parties to the Convention or the Protocol or both instruments.

II) These two international legal instruments apply to persons who are refugees as

therein defined. The assessment as to who is a refugee, i.e. the determination of refugee status

under the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol, is incumbent upon the Contracting State in

whose territory the refugee applies for recognition of refugee status.

III) Both the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol provide for cooperation between the

The Contracting States and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. This

co-operation extends to the determination of refugee status, according to arrangements made in

the various Contracting States.

IV) The Executive Committee of the High Commissioner's Programme at its twenty-eighth

session requested the Office of the High Commissioner “to consider the possibility of issuing – for

the guidance of Governments – a handbook relating to procedures and criteria for determining

refugee status”. The first edition of the Handbook was issued by my Division in September 1979

in response to this request by the Executive Committee. Since then the Handbook has been

regularly reprinted to meet the increasing demands of government officials, academics, and

lawyers concerned with refugee problems. The present edition updates information concerning

accessions to the international refugee instruments including details of declarations on the

geographical applicability of the 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol.

V) The segment of this Handbook on the criteria for determining refugee status breaks down

and explains the various components of the definition of a refugee set out in the 1951 Convention

and the 1967 Protocol. The explanations are based on the knowledge accumulated by the High

Commissioner's Office over some 25 years, since the entry into force of the 1951 Convention on

21 April 1954. The practice of States is taken into account as are exchanges of views between

the Office and the competent authorities of Contracting States, and the literature devoted to the

subject over the last quarter of a century. As the Handbook has been conceived as a practical

guide and not as a treatise on refugee law, references to literature, etc. have purposely been

omitted.

VI) Concerning procedures for the determination of refugee status, the writers of the

Handbook has been guided chiefly by the principles defined in this respect by the Executive

Committee itself. Use has naturally also been made of the knowledge available concerning the

practice of States.

VII) The Handbook is meant for the guidance of government officials concerned with the

determination of refugee status in the various Contracting States. It is hoped that it will also be of

interest and useful to all those concerned with refugee problems.

Michel Moussalli

Director of International Protection

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

INTRODUCTION – International instruments defining the term “refugee”

A. Early instruments (1921-1946)

1. Early in the twentieth century, the refugee problem became the concern of the

international community, which, for humanitarian reasons, began to assume responsibility for

protecting and assisting refugees.

2. The pattern of international action on behalf of refugees was established by the League

of Nations and led to the adoption of several international agreements for their benefit.

These instruments are referred to in Article 1 A (1) of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status

of Refugees (see paragraph 32 below).

3. The definitions in these instruments relate each category of refugees to their national

origin, the territory that they left, and the lack of diplomatic protection from their former home

country. With this type of definition “by categories” interpretation was simple and caused no great

difficulty in ascertaining who was a refugee.

4. Although few persons covered by the terms of the early instruments are likely to request

a formal determination of refugee status at present.. such cases could occasionally arise.

They are dealt with below in Chapter II, A. Persons who meet the definitions of international

instruments before the 1951 Convention are usually referred to as “statutory refugees”. B. 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees

5. Soon after the Second World War, as the refugee problem had not been solved, the need was felt for a new international instrument to define the legal status of refugees. Instead of ad hoc

agreements adopted concerning specific refugee situations, there was a call for an instrument

containing a general definition of who was to be considered a refugee. The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees was adopted by a Conference of Plenipotentiaries of the United Nations

on 28 July 1951 and entered into force on 21 April 1954. In the following paragraphs, it is referred to as “the 1951 Convention”. (The text of the 1951 Convention will be found in Annex II.)

C. Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees

6. According to the general definition contained in the 1951 Convention, a refugee is

a person who:

“As a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951 and owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted … is outside his country of nationality …”

7. The 1951 dateline originated in the wish of Governments, at the time the Convention was adopted, to limit their obligations to refugee situations that were known to exist at that time, or to

those which might subsequently arise from events that had already occurred.1

8. With the passage of time and the emergence of new refugee situations, the need was increasingly felt to make the provisions of the 1951 Convention applicable to such new refugees.

As a result, a Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees was prepared. After consideration by the General Assembly of the United Nations, it was opened for accession on 31 January 1967 and

entered into force on 4 October 1967.

9. By accession to the 1967 Protocol, States undertake to apply the substantive provisions of the 1951 Convention to refugees as defined in the Convention, but without the 1951 dateline.

Although related to the Convention in this way, the Protocol is an independent instrument, accession to which is not limited to States parties to the Convention.

The 1951 Convention also provides for the possibility of introducing a geographic limitation (see paragraphs 108 to 110 below).

10. In the following paragraphs, the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees is referred to as “the 1967 Protocol”. (The text of the Protocol will be found in Annex III.)

11. At the time of writing, 78 States are parties to the 1951 Convention or the 1967 Protocol or both instruments. (A list of the States parties will be found in Annex IV.) D. Main provisions of the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol

12. The 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol contain three types of provisions: (i) Provisions giving the basic definition of who is (and who is not) a refugee and who, having been a refugee, has ceased to be one. The discussion and interpretation of these provisions constitute the main body of the present Handbook, intended for the guidance of those

whose task it is to determine refugee status.

(ii) Provisions that define the legal status of refugees and their rights and duties in their country of refuge. Although these provisions do not influence the process of determination of refugee status, the authority entrusted with this process should be aware of them, for its decision

may indeed have far-reaching effects for the individual or family concerned.

(iii) Other provisions deal with the implementation of the instruments from the administrative and diplomatic standpoint. Article 35 of the 1951 Convention and Article 11 of the 1967 Protocol contain an undertaking by the Contracting States to co-operate with the Office of the

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in the exercise of its functions and, in particular, to facilitate its duty of supervising the application of the provisions of these instruments.

E. Statute of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

13. The instruments described above under A-C define the persons who are to be considered refugees and require the parties to accord a certain status to refugees in their

respective territories.

14. according to a decision of the General Assembly, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (“UNHCR”) was established on 1 January 1951. The Statute of the office is annexed to Resolution 428 (V), adopted by the General Assembly on 14 December

1950. According to the Statute, the High Commissioner is called upon – inter alia – to provide international protection, under the auspices of the United Nations, to refugees falling within the competence of his Office.

15. The Statute contains definitions of those persons to whom the High Commissioner's competence extends, which are very close to, though not identical with, the definition contained in

the 1951 Convention. Under these definitions, the High Commissioner is competent for refugees irrespective of any dateline2 or geographic limitation.3

16. Thus, a person who meets the criteria of the UNHCR Statute qualifies for the protection of the United Nations provided by the High Commissioner, regardless of whether or not he is in a country that is a party to the 1951 Convention or the 1967 Protocol or whether or not he has been recognized by his host country as a refugee under either of these instruments. Such refugees, being within the High Commissioner's mandate, are usually referred to as “mandate

refugees”.

17. From the foregoing, it will be seen that a person can simultaneously be both a mandate

refugee and a refugee under the 1951 Convention or the 1967 Protocol. He may, however, be in a country that is not bound by either of these instruments, or he may be excluded from recognition as a Convention refugee by the application of the dateline or the geographic

2 See paragraphs 35 and 36 below.

3 See paragraphs 108 and 110 below. limitation. In such cases, he would still qualify for protection by the High Commissioner under the

terms of the Statute.

18. The above-mentioned Resolution 428 (V) and the Statute of the High Commissioner's Office call for cooperation between Governments and the High Commissioner's Office in dealing with refugee problems. The High Commissioner is designated as the authority charged with

providing inter-national protection to refugees, and is required inter alia to promote the conclusion and ratification of international conventions for the protection of refugees, and to supervise their application.

19. Such cooperation, combined with his supervisory function, forms the basis for the High Commissioner's fundamental interest in the process of determining refugee status under the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol. The part played by the High Commissioner is reflected, to

varying degrees, in the procedures for the determination of refugee status established by several Governments.

F. Regional instruments relating to refugees

20. In addition to the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol, and the Statute of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, there are several regional agreements,

conventions, and other instruments relating to refugees, particularly in Africa, the Americas, and Europe. These regional instruments deal with such matters as the granting of asylum, travel documents and travel facilities, etc. Some also contain a definition of the term “refugee”, or of

persons entitled to asylum.

21. In Latin America, the problem of diplomatic and territorial asylum is dealt with in several regional instruments including the Treaty on International Penal Law, (Montevideo, 1889); the

Agreement on Extradition, (Caracas, 1911); the Convention on Asylum, (Havana, 1928); the Convention on Political Asylum, (Montevideo, 1933); the Convention on Diplomatic Asylum,

(Caracas, 1954); and the Convention on Territorial Asylum, (Caracas, 1954).

22. A more recent regional instrument is the Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, adopted by the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the Organization of African Unity on 10 September 1969. This Convention contains a definition of the

The term “refugee”, consists of two parts: the first part is identical to the definition in the 1967 Protocol (i.e. the definition in the 1951 Convention without the dateline or geographic limitation). The second part applies the term “refugee” to every person who, owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination, or events seriously disturbing public order in either part or the whole of his country of origin or nationality, is

compelled to leave his place of habitual residence to seek refuge in another place outside his country of origin or nationality”.

23. The present Handbook deals only with the determination of refugee status under the two international instruments of universal scope: the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol. G. Asylum and the treatment of refugees

24. The Handbook does not deal with questions closely related to the determination of refugee status e.g. the granting of asylum to refugees or the legal treatment of refugees after they have been recognized as such.

25. Although there are references to asylum in the Final Act of the Conference of Plenipotentiaries as well as in the Preamble to the Convention, the granting of asylum is not dealt with in the 1951 Convention or the 1967 Protocol. The High Commissioner has always pleaded for a generous asylum policy in the spirit of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Declaration on Territorial Asylum, adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations on 10

December 1948 and 14 December 1967 respectively.

26. Concerning the treatment within the territory of States, this is regulated as regards refugees by the main provisions of the 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol (see paragraph 12(ii) above). Furthermore, attention should be drawn to Recommendation E contained in the Final Act of the Conference of Plenipotentiaries which adopted the 1951 Convention:

“The Conference Expresses the hope that the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees will have value as an example exceeding its contractual scope and that all nations will be guided by it in granting

so far as possible to persons in their territory as refugees and who would not be covered by the terms of the Convention, the treatment for which it provides.”

27. This recommendation enables States to solve such problems as may arise concerning persons who are not regarded as fully satisfying the criteria of the definition of the term “refugee”.

PART ONE – Criteria for the Determination of Refugee Status

CHAPTER I – GENERAL PRINCIPLES

28. A person is a refugee within the meaning of the 1951 Convention as soon as he fulfills the criteria contained in the definition. This would necessarily occur before the time at which his

refugee status is formally determined. Recognition of his refugee status does not, therefore, make him a refugee but declares him to be one. He does not become a refugee because of recognition

but is recognized because he is a refugee.

29. Determination of refugee status is a process that takes place in two stages. Firstly, it is necessary to ascertain the relevant facts of the case. Secondly, the definitions in the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol have to be applied to the facts thus ascertained.

30. The provisions of the 1951 Convention defines who is a refugee and consist of three parts, which have been termed respectively “inclusion”, “cessation” and “exclusion” clauses.

31. The inclusion clauses define the criteria that a person must satisfy to be a refugee. They form the positive basis upon which the determination of refugee status is made. The so-called cessation and exclusion clauses have a negative significance; the former indicates the conditions under which a refugee ceases to be a refugee and the latter enumerates the

circumstances in which a person is excluded from the application of the 1951 Convention

although meeting the positive criteria of the inclusion clauses.

CHAPTER II – INCLUSION CLAUSES

A. Definitions

(1) Statutory Refugees

32. Article 1 A (1) of the 1951 Convention deals with statutory refugees, i.e. persons considered to be refugees under the provisions of international instruments preceding the Convention. This provision states that: For the present Convention, the term 'refugee' shall apply to any person who:

(1) Has been considered a refugee under the Arrangements of 12 May 1926 and 30 June

1928 or under the Conventions of 28 October 1933 and 10 February 1938, the Protocol of 14 September 1939 or the Constitution of the International Refugee Organization; Decisions of non-eligibility taken by the International Refugee Organization during the period of its

activities shall not prevent the status of refugees being accorded to persons who fulfill the conditions of paragraph 2 of this section.”

33. The above enumeration is given to provide a link with the past and to ensure the continuity of international protection of refugees who became the concern of the international community in various earlier periods. As already indicated (para. 4 above), these instruments have by now lost much of their significance, and a discussion of them here would be of little practical value. However, a person who has been considered a refugee under the terms of any of these instruments is automatically a refugee under the 1951 Convention. Thus, a holder of a so-called “Nansen Passport”4 or a “Certificate of Eligibility” issued by the International RefugeeThe organization must be considered a refugee under the 1951 Convention unless one of the cessation clauses has become applicable to his case or he is excluded from the application of the Convention by one of the exclusion clauses. This also applies to a surviving child of a statutory refugee.

Nansen Passport": a certificate of identity for use as a travel document, issued to refugees under the provisions of prewar instruments.

(2) General definition in the 1951 Convention

34. According to Article 1 A (2) of the 1951 Convention the term “refugee” shall apply to any person who:

“As a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951 and owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or

political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable

or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.

This general definition is discussed in detail below.

B. Interpretation of terms

(1) “Events occurring before 1 January 1951”

35. The origin of this 1951 dateline is explained in paragraph 7 of the Introduction. As a result of the 1967 Protocol, this dateline has lost much of its practical significance. An interpretation of the word “events” is therefore of interest only in the small number of States parties to 1951

The convention that is not also party to the 1967 Protocol.5

36. The word “events” is not defined in the 1951 Convention but was understood to mean happenings of major importance involving territorial or profound political changes as well as systematic programs of persecution which are after-effects of earlier changes”.6

The dateline refers to “events” as a result of which, and not to the date on which, a person becomes a refugee, nor does it apply to the date on which he left his country. A refugee may have left his country

before or after the datelines, provided that his fear of persecution is due to “events” that occurred

before the dateline or to after-effects occurring at a later date as a result of such events.7

(2) “well-founded fear of being persecuted”

(a) General analysis

37. The phrase “well-founded fear of being persecuted” is the key phrase of the definition. It

reflects the views of its authors as to the main elements of refugee characters. It replaces the earlier method of defining refugees by categories (i.e. persons of a certain origin not enjoying the

protection of their country) with the general concept of “fear” for a relevant motive. Since fear is subjective, the definition involves a subjective element in the person applying for recognition as

a refugee. Determination of refugee status will therefore primarily require an evaluation of the applicant's statements rather than a judgment on the situation prevailing in his country of origin.

38. To the element of fear – a state of mind and a subjective condition – is added the qualification “well-founded”. This implies that it is not only the frame of mind of the person concerned that determines his refugee status, but that this frame of mind must be supported by

an objective situation. The term “well-founded fear” therefore contains a subjective and an objective element, and in determining whether well-founded fear exists, both elements must be taken into consideration.

39. It may be assumed that, unless he seeks adventure or just wishes to see the world,

a person would not normally abandon his home and country without some compelling reason. There may be many reasons that are compelling and understandable, but only one motive has

5

See Annex IV.

6

UN Document E/1618 page 39.

7

Loc. cit. been singled out to denote a refugee. The expression “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted” – for the reasons stated – by indicating a specific motive automatically makes all other reasons for escape irrelevant to the definition. It rules out such persons as victims of famine or natural disaster unless they also have a well-founded fear of persecution for one of the reasons stated. Such other motives may not, however, be altogether irrelevant to the process of determining refugee status, since all the circumstances need to be taken into account for a proper understanding of the applicant's case.

40. An evaluation of the subjective element is inseparable from an assessment of the personality of the applicant, since the psychological reactions of different individuals may not be the same in identical conditions. One person may have strong political or religious convictions, the disregard of which would make his life intolerable; another may have no such strong convictions. One person may make an impulsive decision to escape; another may carefully plan his departure.

41. Due to the importance that the definition attaches to the subjective element, an assessment of credibility is indispensable where the case is not sufficiently clear from the facts on record. It will be necessary to take into account the personal and family background of the applicant, his membership in a particular racial, religious, national, social, or political group, his interpretation of his situation, and his personal experiences – in other words, everything that may serve to indicate that the predominant motive for his application is fear. Fear must be reasonable. Exaggerated fear, however, may be well-founded if, in all the circumstances of the

case, such a state of mind can be regarded as justified.

42. As regards the objective clement, it is necessary to evaluate the statements made by the applicant. The competent authorities that are called upon to determine refugee status are not required to pass judgment on conditions in the applicant's country of origin. The applicant's statements cannot, however, be considered in the abstract, and must be viewed in the context of the relevant background situation. A knowledge of conditions in the applicant's country of origin – while not a primary objective – is an important element in assessing the applicant's credibility. In general, the applicant's fear should be considered well-founded if he can establish, to a reasonable degree, that his continued stay in his country of origin has become intolerable to him for the reasons stated in the definition, or would for the same reasons be intolerable if he

returned there.

43. These considerations need not necessarily be based on the applicant's own experience. What, for example, happened to his friends and relatives and other members of the same racial or social group may well show that his fear that sooner or later he also will become a

victim of persecution is well-founded. The laws of the country of origin, and particularly how they are applied, will be relevant. The situation of each person must, however, be assessed on its own merits. In the case of a well-known personality, the possibility of persecution may be greater than in the case of a person in obscurity. All these factors, e.g. a person's character, his background, his influence, his wealth, or his outspokenness, may lead to the conclusion that his fear of persecution is “well-founded”.

44. While refugee status must normally be determined on an individual basis, situations have also arisen in which entire groups have been displaced under circumstances indicating that members of the group could be considered individually refugees. In such situations the need

Assisting is often extremely urgent and it may not be possible for purely practical reasons to carry out an individual determination of refugee status for each member of the group. Recourse has therefore been had to so-called “group determination” of refugee status, whereby

each member of the group is regarded prima facie (i.e. in the absence of evidence to the contrary) as a refugee.

45. Apart from the situations of the type referred to in the preceding paragraph, an applicant for refugee status must normally show a good reason why he individually fears persecution. It may be assumed that a person has a well-founded fear of being persecuted if he has already been the victim of persecution for one of the reasons enumerated in the 1951 Convention. However, the word “fear” refers not only to persons who have been persecuted but also to those who wish to avoid a situation entailing the risk of persecution.

46. The expressions “fear of persecution” or even “persecution” are usually foreign to a refugee's normal vocabulary. A refugee will indeed only rarely invoke “fear of persecution” in these terms, though it will often be implicit in his story. Again, while a refugee may have very definite opinions for which he has had to suffer, he may not, for psychological reasons, be able to describe his experiences and situation in political terms.

47. A typical test of the well-founded fear will arise when an applicant owns a valid national passport. It has sometimes been claimed that possession of a passport signifies that the issuing authorities do not intend to persecute the holder, for otherwise, they would not have issued a passport to him. Though this may be true in some cases, many persons

have used a legal exit from their country as the only means of escape without ever having revealed their political opinions, a knowledge of which might place them in a dangerous situation vis-à-vis the authorities.

48. Possession of a passport cannot therefore always be considered as evidence of loyalty on the part of the holder, or as an indication of the absence of fear. A passport may even be issued to a person who is undesired in his country of origin, with the sole purpose of securing his

departure, and there may also be cases where a passport has been obtained surreptitiously. In conclusion, therefore, the mere possession of a valid national passport is no bar to refugee

status.

49. If, on the other hand, an applicant, without good reason, insists on retaining a valid passport of a country of whose protection he is allegedly unwilling to avail himself, this may cast doubt on the validity of his claim to have “well-founded fear”. Once recognized, a refugee should not normally retain his national passport.

50. There may, however, be exceptional situations in which a person fulfilling the criteria of refugee status may retain his national passport or be issued a new one by the authorities of his country of origin under special arrangements. Particularly where such arrangements do not

imply that the holder of the national passport is free to return to his country without prior permission, they may not be incompatible with refugee status. (b) Persecution

51. There is no universally accepted definition of “persecution”, and various attempts to formulate such a definition have met with little success. From Article 33 of the 1951 Convention, it may be inferred that a threat to life or freedom on account of race, religion, nationality, political

opinion, or membership of a particular social group is always persecution. Other serious violations of human rights – for the same reasons – would also constitute persecution.

52. Whether other prejudicial actions or threats would amount to persecution will depend on

the circumstances of each case, including the subjective element to which reference has been made in the preceding para. graphs. The subjective character of fear of persecution requires an evaluation of the opinions and feelings of the person concerned. It is also in the light of such opinions and feelings that any actual or anticipated measures against him must necessarily be viewed. Due to variations in the psychological make-up of individuals and the circumstances of

each case, interpretations of what amounts to persecution are bound to vary.

53. In addition, an applicant may have been subjected to various measures not in themselves amounting to persecution (e.g. discrimination in different forms), in some cases combined with other adverse factors (e.g. general atmosphere of insecurity in the country of origin). In such

situations, the various elements involved may, if taken together, produce an effect on the mind of the applicant that can reasonably justify a claim to a well-founded fear of persecution on cumulative grounds”. Needless to say, it is not possible to lay down a general rule as to what cumulative reasons can give rise to a valid claim for refugee status. This will necessarily depend on all the circumstances, including the particular geographical, historical and ethnological context.

(c) Discrimination

54. Differences in the treatment of various groups do indeed exist to a greater or lesser extent in many societies. Persons who receive less favorable treatment as a result of such differences are not necessarily victims of persecution. It is only in certain circumstances that

discrimination will amount to persecution. This would be so if measures of discrimination lead to consequences of a substantially prejudicial nature for the person concerned, e.g. serious restrictions on his right to earn his livelihood, his right to practice his religion, or his access to

normally available educational facilities.

55. Where measures of discrimination are, in themselves, not of a serious character, they may nevertheless give rise to a reasonable fear of persecution if they produce, in the mind of the person concerned, a feeling of apprehension and insecurity as regards his future existence. Whether or not such measures of discrimination in themselves amount to persecution must be determined in light of all the circumstances. A claim to fear of persecution will of course be stronger where a person has been the victim of several discriminatory measures of this type

and where there is thus a cumulative element involved.8 (d) Punishment

56. Persecution must be distinguished from punishment for a common-law offense. Persons fleeing from prosecution or punishment for such an offense are not normally refugees. It should be recalled that a refugee is a victim – or potential victim – of injustice, not a fugitive from justice.

57. The above distinction may, however, occasionally be obscured. In the first place, a person guilty of a common-law offense may be liable to excessive punishment, which may amount to persecution within the meaning of the definition. Moreover, penal prosecution for a reason mentioned in the definition (for example, in respect of “illegal” religious instruction given to a child) may in itself amount to persecution.

58. Secondly, there may be cases in which a person, besides fearing prosecution or punishment for a common-law crime, may also have a “well-founded fear of persecution”. In such cases, the person concerned is a refugee. It may, however, be necessary to consider whether the

crime in question is not of such a serious character as to bring the applicant within the scope of one of the exclusion clauses.9

59. To determine whether prosecution amounts to persecution, it will also be necessary to refer to the laws of the country concerned, for it is possible for law not to conform with accepted human rights standards. More often, however, it may not be the law but its application that is discriminatory. Prosecution for an offense against “public order”, e.g. for

distribution of pamphlets, could for example be a vehicle for the persecution of the individual on the grounds of the political content of the publication

60. In such cases, due to the obvious difficulty involved in evaluating the laws of another country, national authorities may frequently have to take decisions by using their national legislation as a yardstick. Moreover, recourse may usefully be had to the principles set out in the

various international instruments relating to human rights, in particular, the International Covenants on Human Rights, which contain binding commitments for the States parties and are instruments to which many States parties to the 1951 Convention have acceded. (e) Consequences of unlawful departure or unauthorized stay outside the country of origin

61. The legislation of certain States imposes severe penalties on nationals who unlawfully depart from the country or remain abroad without authorization. Where there is reason See also paragraph 53. See paragraphs 144 to 156. to believe that a person, due to his illegal departure or unauthorized stay abroad is liable to such severe penalties his recognition as a refugee will be justified if it can be shown that his motives for leaving or remaining outside the country are related to the reasons enumerated in Article 1 A (2) of the 1951 Convention (see paragraph 66 below). (f) Economic migrants distinguished from refugees

62. A migrant is a person who, for reasons other than those contained in the definition, voluntarily leaves his country to take up residence elsewhere. He may be moved by the desire for change or adventure, or my family or other reasons of a personal nature. If he is moved

exclusively by economic considerations, he is an economic migrant and not a refugee

63. The distinction between an economic migrant and a refugee is, however, sometimes blurred in the same way as the distinction between economic and political measures in an applicant's country of origin is not always clear. Behind economic measures affecting a person's livelihood, there may be racial, religious, or political aims or intentions directed against a particular group. Where economic measures destroy the economic existence of a particular section of the population (e.g. withdrawal of trading rights from, or discriminatory or excessive taxation of, a specific ethnic or religious group), the victims may according to the circumstances become refugees on leaving the country.

64. Whether the same would apply to victims of general economic measures (i.e. those that are applied to the whole population without discrimination) would depend on the circumstances of the case. Objections to general economic measures are not by themselves good reasons for claiming refugee status. On the other hand, what appears, at first sight, to be primarily an economic motive for departure may in reality also involve a political element, and it may be the political opinions of the individual that expose him to serious consequences, rather than his

objections to the economic measures themselves. (g) Agents of persecution

65. Persecution is normally related to action by the authorities of a country. It may also emanate from sections of the population that do not respect the standards established by the laws of the country concerned. A case in point may be religious intolerance, amounting to persecution, in a country otherwise secular, but where sizeable fractions of the population do not respect the religious beliefs of their neighbors. Where serious discriminatory or other offensive acts are committed by the local populace, they can be considered persecution if they are knowingly tolerated by the authorities, or if the authorities refuse, or prove unable, to offer effective protection.

(3) “for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” (a) General analysis

66. To be considered a refugee, a person must show a well-founded fear of persecution for one of the reasons stated above. It is immaterial whether the persecution arises from any single one of these reasons or a combination of two or more of them. Often the applicant himself may not be aware of the reasons for the persecution feared. It is not, however,

his duty to analyze his case to such an extent as to identify the reasons in detail

67. It is for the examiner, when investigating the facts of the case, to ascertain the reason or reasons for the persecution feared and to decide whether the definition in the 1951 Convention is met in this respect. The reasons for persecution under these various headings will frequently overlap. Usually, there will be more than one clement combined in one person, e.g. a political opponent who belongs to a religious or national group, or both, and the combination of such reasons in his person may be relevant in evaluating his well-founded fear.

(b) Race

68. Race, in the present connexion, has to be understood in its widest sense to include all kinds of ethnic groups that are referred to as “races” in common usage. Frequently it will also entail membership of a specific social group of common descent forming a minority within a larger

population. Discrimination for reasons of race has found worldwide condemnation as one of the most striking violations of human rights. Racial discrimination, therefore, represents an important element in determining the existence of persecution.

69. Discrimination on racial grounds will frequently amount to persecution in the sense of the 1951 Convention. This will be the case if, as a result of racial discrimination, a person's human dignity is affected to such an extent as to be incompatible with the most elementary and inalienable human rights, or where the disregard of racial barriers is subject to serious consequences.

70. The mere fact of belonging to a certain racial group will normally not be enough to substantiate a claim for refugee status. There may, however, be situations where due to particular circumstances affecting the group, such membership will in itself be sufficient ground to fear persecution.

(c) Religion

71. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Human Rights Covenant proclaim the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion, which right includes the freedom of a person to change his religion and his freedom to manifest it in public or private, in teaching, practice, worship, and observance.

72. Persecution for “reasons of religion” may assume various forms, e.g. prohibition of membership of a religious community, of worship in private or in public, of religious instruction, or serious measures of discrimination imposed on persons because they practice their religion or belong to a particular religious community.

73. Mere membership in a particular religious community will normally not be enough to substantiate a claim for refugee status. There may, however, be special circumstances where mere membership can be sufficient ground. (d) Nationality

74. The term “nationality” in this context is not to be understood only as “citizenship”. It refers also to membership of an ethnic or linguistic group and may occasionally overlap with the term race”. Persecution for reasons of nationality may consist of adverse attitudes and measures directed against a national (ethnic, linguistic) minority and in certain circumstances, the fact of belonging to such a minority may in itself give rise to a well-founded fear of persecution.

75. The co-existence within the boundaries of a State of two or more national (ethnic, linguistic) groups may create situations of conflict and also situations of persecution or danger of persecution. It may not always be easy to distinguish between persecution for reasons of nationality and persecution for reasons of political opinion when a conflict between national groups is combined with political movements, particularly where a political movement is identified

with a specific “nationality”.

76. Whereas in most cases persecution for reason of nationality is feared by persons belonging to a national minority, there have been many cases in various continents where a person belonging to a majority group may fear persecution by a dominant minority. (e) Membership in a particular social group

77. A “particular social group” normally comprises persons of similar backgrounds, habits, or social status. A claim to fear persecution under this heading may frequently overlap with a claim to fear persecution on other grounds, i.e. race, religion, or nationality.

78. Membership of such a particular social group may be at the root of persecution because there is no confidence in the group's loyalty to the Government or because of the political outlook, antecedents or economic activity of its members, or the very existence of the social group as

such is held to be an obstacle to the Government's policies.

79. Mere membership of a particular social group will not normally be enough to substantiate a claim for refugee status. There may, however, be special circumstances where mere membership can be a sufficient ground to fear persecution. (f) Political opinion

80. Holding political opinions different from those of the Government is not in itself a ground for claiming refugee status, and an applicant must show that he has a fear of persecution for holding such opinions. This presupposes that the applicant holds opinions not tolerated by the

authorities, which are critical of their policies or methods. It also presupposes that such opinions have come to the notice of the authorities or are attributed by them to the applicant. The political

opinions of a teacher or writer may be more manifest than those of a person in a less exposed position. The relative importance or tenacity of the applicant's opinions – in so far as this can be established from all the circumstances of the case – will also be relevant.

81. While the definition speaks of persecution “for reasons of political opinion” it may not always be possible to establish a causal link between the opinion expressed and the related measures suffered or feared by the applicant. Such measures have only rarely been based expressly on “opinion”. More frequently, such measures take the form of sanctions for alleged criminal acts against the ruling power. It will, therefore, be necessary to establish the applicant's political opinion, which is at the root of his behavior, and the fact that it has led or may lead to

the persecution that he claims to fear.

82. As indicated above, persecution “for reasons of political opinion” implies that an applicant holds an opinion that either has been expressed or has come to the attention of the authorities. There may, however, also be situations in which the applicant has not given any expression to his opinions. Due to the strength of his convictions, however, it may be reasonable to assume that his opinions will sooner or later find expression and that the applicant will, as a result, come into conflict with the authorities. Where this can reasonably be assumed, the applicant can be considered to have fear of persecution for reasons of political opinion.

83. An applicant claiming fear of persecution because of political opinion need not show that the authorities of his country of origin knew of his opinions before he left the country. He may have concealed his political opinion and never suffered any discrimination or persecution.

However, the mere fact of refusing to avail himself of the protection of his Government, or a refusal to return, may disclose the applicant's true state of mind and give rise to fear of persecution. In such circumstances, the test of well-founded fear would be based on an assessment of the consequences that an applicant having certain political dispositions would

have to face if he returned. This applies particularly to the so-called refugee “sur place

84. Where a person is subject to prosecution or punishment for a political offense, a distinction may have to be drawn according to whether the prosecution is for political opinion or politically-motivated acts. If the prosecution pertains to a punishable act committed out of political motives, and if the anticipated punishment conforms with the general law of the country concerned, fear of such prosecution will not in itself make the applicant a refugee.

85. Whether a political offender can also be considered a refugee will depend upon various other factors. Prosecution for an offense may depending upon the circumstances, be a pretext for punishing the offender for his political opinions or the expression thereof. Again, there may be a reason to believe that a political offender would be exposed to excessive or arbitrary punishment for the alleged offense. Such excessive or arbitrary punishment will amount to persecution. See paragraphs 94 to 96

86. In determining whether a political offender can be considered a refugee, regard should also be had to the following elements: the personality of the applicant, his political opinion, the motive behind the act, the nature of the act committed, the nature of the prosecution and its motives; finally, also, the nature of the law on which the prosecution is based. These elements may go to show that the person concerned has a fear of persecution and not merely a fear of prosecution and punishment – within the law – for an act committed by him. (4) “is outside the country of his nationality” (a) General analysis

87. In this context, “nationality” refers to “citizenship”. The phrase “is outside the country of his nationality” relates to persons who have a nationality, distinct from stateless persons. In the majority of cases, refugees retain the nationality of their country of origin.

88. It is a general requirement for refugee status that an applicant who has a nationality be outside the country of his nationality. There are no exceptions to this rule. International protection cannot come into play as long as a person is within the territorial jurisdiction of his home

country.

89. Where, therefore, an applicant alleges fear of persecution concerning the country of his nationality, it should be established that he does possess the nationality of that country.

There may, however, be uncertainty as to whether a person has a nationality. He may not know himself, or he may wrongly claim to have a particular nationality or to be stateless. Where his nationality cannot be established, his refugee status should be determined similarly to that of a stateless person, i.e. instead of the country of his nationality, the country of his former habitual residence will have to be taken into account. (See paragraphs 101 to 105 below.)

90. As mentioned above, an applicant's well-founded fear of persecution must be concerning the country of his nationality. As long as he has no fear concerning the country of his nationality, he can be expected to avail himself of that country's protection. He is not in need of

international protection and is therefore not a refugee.

91. The fear of being persecuted need not always extend to the whole territory of the refugee's country of nationality. Thus in ethnic clashes or in cases of grave disturbances involving civil war conditions, persecution of a specific ethnic or national group may occur in only one part

of the country. In such situations, a person will not be excluded from refugee status merely because he could have sought refuge in another part of the same country if under all the circumstances it would not have been reasonable to expect him to do so

92. The situation of persons having more than one nationality is dealt with in paragraphs 106 and 107 below

93. Nationality may be proved by the possession of a national passport. Possession of such a passport creates a prima facie presumption that the holder is a national of the country of issue unless the passport itself states otherwise. A person holding a passport showing him to be

a national of the issuing country, but who claims that he does not possess that country's nationality, must substantiate his claim, for example, by showing that the passport is a so-called passport of convenience” (a regular national passport that is sometimes issued by a

national authority to non-nationals). However, a mere assertion by the holder that the passport

11 In certain countries, particularly in Latin America, there is a custom of “diplomatic asylum", i.e.

granting refuge to political fugitives in foreign embassies. While a person thus sheltered may be considered to be outside his country's jurisdiction, he is not outside its territory and cannot, therefore, be considered under the terms of the 1951 Convention. The former notion of the

“extraterritoriality" of embassies has lately been replaced by the term “inviolability" used in the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations.

was issued to him as a matter of convenience for travel purposes only is not sufficient to rebut the presumption of rationality. In certain cases, it might be possible to obtain information from the authority that issued the passport. If such information cannot be obtained, or cannot be obtained

within a reasonable time, the examiner will have to decide on the credibility of the applicant's assertion in weighing all other elements of his story. (b) Refugees “sur place

94. The requirement that a person must be outside his country to be a refugee does not mean that he must necessarily have left that country illegally, or even that he must have left it on account of well-founded fear. He may have decided to ask for recognition of his refugee status

after having already been abroad for some time. A person who was not a refugee when he left his country, but who becomes a refugee at a later date, is called a refugee “sur place”.

95. A person becomes a refugee “sur place” due to circumstances arising in his country of origin during his absence. Diplomats and other officials serving abroad, prisoners of war, students, migrant workers, and others have applied for refugee status during their residence abroad and have been recognized as refugees.

96. A person may become a refugee “sur place” as a result of his actions, such as associating with refugees already recognized or expressing his political views in his country of residence. Whether such actions are sufficient to justify a well-founded fear of persecution must be determined by a careful examination of the circumstances. Regard should be had in particular to whether such actions may have come to the notice of the authorities of the person's country of origin and how they are likely to be viewed by those authorities. (5) “and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country

97. Unlike the phrase dealt with under (6) below, the present phrase relates to persons who have a nationality. Whether unable or unwilling to avail himself of the protection of his Government, a refugee is always a person who does not enjoy such protection

98. Being unable to avail himself of such protection implies circumstances that are beyond the will of the person concerned. There may, for example, be a state of war, civil war, or other grave disturbance, which prevents the country of nationality from extending protection or makes such protection ineffective. Protection by the country of nationality may also have been denied to the applicant. Such denial of protection may confirm or strengthen the applicant's fear of persecution, and may indeed be an element of persecution.

99. What constitutes a refusal of protection must be determined according to the circumstances of the case. If it appears that the applicant has been denied services (e.g., refusal of a national passport or extension of its validity, or denial of admittance to the home territory)

normally accorded to his co-nationals, this may constitute a refusal of protection within the definition. 100. The term unwilling refers to refugees who refuse to accept the protection of the Government of the country of their nationality.12 It is qualified by the phrase “owing to such fear”.

When a person is willing to avail himself of the protection of his home country, such willingness would normally be incompatible with a claim that he is outside that country “owing to well-founded

fear of persecution”. Whenever the protection of the country of nationality is available, and there is no ground-based or well-founded fear of refusing it, the person concerned does not need international protection and is not a refugee. 12 UN Document E/1618, p. 39. (6) “or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual

residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it

101. This phrase, which relates to stateless refugees, is parallel to the preceding phrase, which concerns refugees who have a nationality. In the case of stateless refugees, the “country of

nationality” is replaced by “the country of his former habitual residence”, and the expression unwilling to avail himself of the protection…” is replaced by the words “unwilling to return to it”. In the case of a stateless refugee, the question of “availment of protection” of the country of his

former habitual residence does not, of course, arise. Moreover, once a stateless person has abandoned the country of his former habitual residence for the reasons indicated in the definition,

he is usually unable to return

102. It will be noted that not all stateless persons are refugees. they must be outside the country of their former habitual residence for the reasons indicated in the definition. Where these reasons do not exist, the stateless person is not a refugee

103. Such reasons must be examined about the country of “former habitual residence” regarding which fear is alleged. This was defined by the drafters of the 1951 Convention as “the country in which he had resided and where he had suffered or fears he would suffer persecution if

he returned”.13

104. A stateless person may have more than one country of former habitual residence, and he may have a fear of persecution in more than one of them. The definition does not require that he satisfies the criteria for all of them

105. Once a stateless person has been determined a refugee in “the country of his former habitual residence”, any further change of country of habitual residence will not affect his refugee status. (7) Dual or multiple nationalities Article 1 A (2), paragraph 2, of the 1951 Convention:

“In the case of a person who has more than one nationality, the term “the country of his nationality” shall mean each of the countries of which he is a national, and a person shall not be deemed to be lacking the protection of the country of his nationality if, without any valid reason based on well-founded fear, he has not availed himself of the protection of one of the

countries of which he is a national

106. This clause, which is largely self-explanatory, is intended to exclude from refugee status all persons with dual or multiple nationalities who can avail themselves of the protection of at least one of the countries of which they are nationals. Wherever available, national protection takes

precedence over international protection

107. In examining the case of an applicant with dual or multiple nationalities, it is necessary, however, to distinguish between the possession of nationality in the legal sense and the

availability of protection by the country concerned. There will be cases where the applicant has the nationality of a country regarding which he alleges no fear, but such nationality may be deemed to be ineffective as it does not entail the protection normally granted to nationals. In such

circumstances, the possession of the second nationality would not be inconsistent with refugee status. As a rule, there should have been a request for, and a refusal of, protection before it can

be established that a given nationality is ineffective. If there is no explicit refusal of protection, the absence of a reply within a reasonable time may be considered a refusal. 13 Loc. cit. (8) Geographical scope

108. At the time when the 1951 Convention was drafted, there was a desire by several States not to assume obligations the extent of which could not be foreseen. This desire led to the inclusion of the 1951 dateline, to which reference has already been made (paragraphs 35 and 36

above). In response to the wish of certain Governments, the 1951 Convention also gave to The Contracting States the possibility of limiting their obligations under the Convention to persons who

had become refugees as a result of events occurring in Europe.

109. Accordingly, Article 1 B of the 1951 Convention states that:

(1) For this Convention, the words “events occurring before 1 January 1951 in Article 1, Section A, shall be understood to mean either (a) “events occurring in Europe before 1 January 1951”; or (b) “events occurring in Europe and elsewhere before 1 January 1951 and each Contracting State shall make a declaration at the time of signature, ratification, or accession, specifying which of these meanings it applies for its obligations under this Convention. (2) Any Contracting State which has adopted alternative (a) may at any time extend its obligations by adopting alternative (b) by utilizing a notification addressed to the SecretaryGeneral of the United Nations

110. Of the States parties to the 1951 Convention, at the time of writing 9 still adhere to alternative (a), “events occurring in Europe”.14 While refugees from other parts of the world frequently obtain asylum in some of these countries, they are not normally accorded, refugee

status under the 1951 Convention.

CHAPTER III – CESSATION CLAUSES

A. General

111. The so-called “cessation clauses” (Article 1 C (1) to (6) of the 1951 Convention) spell out the conditions under which a refugee ceases to be a refugee. They are based on the consideration that international protection should not be granted where it is no longer necessary

or justified.

112. Once a person's status as a refugee has been determined, it is maintained unless he comes within the terms of one of the cessation clauses.15 This strict approach towards the

determination of refugee status results from the need to provide refugees with the assurance that their status will not be subject to constant review in the light of temporary changes – not of a fundamental character – in the situation prevailing in their country of origin

113. Article 1 C of the 1951 Convention provides that: This Convention shall cease to apply to any person falling under the terms of section A if:

(1) He has voluntarily re-availed himself of the protection of the country of his nationality; or (2) Having lost his nationality, he has voluntarily re-acquired it; or (3) He has acquired a new nationality and enjoys the protection of the country of his new nationality, 14 See Annex IV.

15 In some cases refugee status may continue, even though the reasons for such status have ceased to exist. Cf sub-sections (5) and (6) (paragraphs 135 to 139 below)

(4) He has voluntarily re-established himself in the country which he left or outside which he remained owing to fear of persecution; or (5) He can no longer because of the circumstances in connexion with which he has been recognized as a refugee have ceased to exist, continue to refuse to avail himself of the protection of the country of his nationality; Provided that this paragraph shall not apply to a refugee falling under Section A (1) of this Article who can invoke compelling reasons arising out of previous persecution for refusing to avail himself of the protection of the country of nationality

(6) Being a person who has no nationality he is, because of the circumstances in connexion with which he has been recognized as a refugee has ceased to exist, able to return to the country

of his former habitual residence; Provided that this paragraph shall not apply to a refugee falling under section A (1) of this Article who can invoke compelling reasons arising out of previous persecution for refusing to return to the country of his former habitual residence.”

114. Of the six cessation clauses, the first four reflect a change in the situation of the refugee

that has been brought about by himself, namely: (1) voluntary re-availing of national protection (2) voluntary re-acquisition of nationality;

(3) acquisition of a new nationality (4) voluntary re-establishment in the country where persecution was feared

115. The last two cessation clauses, (5) and (6), are based on the consideration that international protection is no longer justified on account of changes in the country where persecution was feared because the reasons for a person becoming a refugee have ceased to

exist.

116. The cessation clauses are negative and are exhaustively enumerated. They should therefore be interpreted restrictively, and no other reasons may be adduced by way of analogy to justify the withdrawal of refugee status. Needless to say, if a refugee, for whatever reason no longer wish to be considered a refugee, there will be no call for continuing to grant

his refugee status and international protection